People lose things when they move.

Losing things is my habitual worry and a worrisome habit. This, I think, is one reason for science’s relentless struggle to control chaos. Or it’s my persistent effort.

Mercifully anxiety over losing things is soothed by the very method that helps not lose things: order, precision. Important things like car registrations and deeds to the house, life insurance, the 15-digit code that identifies software, keys to the back gate, manual for the refrigerator or cell phone, hardware for picture framing or fixing a hose, devices to cover electrical cords running along the floorboards, filters for the humidifier, sticky-backed Velcro for mounting the tollway transponder, attachments for each of the 3 different shop vacs, a wallet I used in the ‘80s when I carried a purse, photos of my great-grandparents. I can put my hands on almost anything I need when the need arrives, because I know where it is, because I stored it in a systematic way.

But I’m not a hoarder, not much of a magpie. Giving bundles to thrift stores is also a stress reliever, an anxiety quieter. Even writing about it has been useful:

… Then she loaded her boxes of winter accessories—scarves, gloves, sweaters, wool socks and boots—into her car and drove them to the Salvation Army. The next day she emptied [her unpacked] suitcase into bags and made the trip again . . . When she climbed a ladder to put the suitcase back into the closet, she took down framed posters she’d been saving to put on the walls after re-painting someday; box games of Monopoly, Uno and Tile Rummy; and a briefcase she’d carried in college. She took them all to the Salvation Army. Then she went through the linen closet and removed fancy lace-edged pillow cases, a stadium blanket, place mats, a table cloth, curtains, guest towels and a box where they’d always put interesting articles clipped from the paper. As she woke each morning she thought about that day’s trip to the donation center and what she would take. Vases, platters, pitchers, trays, salt and pepper shakers. Books, records, nick-nacks, dusty macramé wall art. An empty aquarium, baseball mitts, hanging plant pots. Then some of the smaller pieces of furniture started to go, bookcases and end tables, plant stands, a coat rack. On Sundays, when the collection center wasn’t open, time crawled, she was restless and frustrated, tried to sleep late but couldn’t, glancing often at the black garbage bag waiting by the front door to be taken out first thing Monday.

Dog People 1998

Mostly it hasn’t been clothes in the bags awaiting the next trip to the donation center; I buy most of my clothes there. My jeans march steadily down three shelves in my closet, from best (although bought used) to dog training jeans to garden jeans. It takes several years before a pair can’t even validate its place on the garden jeans shelf, and by then the fabric that remains might be used to patch some of the others. Still, some clothes do go into the donation bag, if I hope the style will never come back, if it attracts and embeds too much dog hair, if it’s too girly (from a time I thought I should try harder), if it doesn’t pass a physical or emotional comfort audition (worn to work for a day to see if I don’t notice wearing it).

Clothes and shoes don’t get lost, they only take up too much of the vital space for arranging other things that might be. Organization. Maybe uber organization. And then re-organizing. The modus to simultaneously facilitate not losing things and to sift out what gets sent to the donation center. This also allows both cars to live inside the garage, allows half my basement to be left bare for dog training, allows two people to cook in a kitchen that only has two counters and two drawers. Order. Authority over chaos. The fundamental anxiety reliever. Shelves, shelf organizers, drawers, drawer organizers, designated and outfitted closets for specific needs from supplies to archives, all-the-same-size boxes with labels. These are some kind of serenity.

But people lose things when they move. Thrown away or given away without remembering. Stashed in a “misc.” box with no other label, and there might be fifteen such boxes, some not unpacked for years (not in my basement). Something loaned and not returned at the previous residence. Something stored in a place no one remembered to pack, an attic or under the stairs. The thing might then forcibly pass the “if you don’t use it in a year, get rid of it” test. But what if it were a photograph or a letter? Do I really want to read any of the letters I wrote to an ex-husband while I was in graduate school in Brooklyn and he was living in our rented shack in San Diego? No, I never will, and I really have considered a bonfire. But the box is labeled, tied with string, and stored where I know it is but won’t see it unless I had to go look for it, which I won’t have to. Why is this important? I can’t say. I just know where it is.

Most of my mother’s slides as well as her mother’s photo albums are put away and labeled, maybe not as archive-protected as they should be in humidity and acid controlled environments. At least they’re not in the basement which gets damp (although a dehumidifier runs nonstop). Most importantly, I know where they are. A large scanning and digital storing project is planned, so they await, along with a box of slide-organization tools—light bar, slide sleeves, slide bins, etc. The un-started status of the project creates no affecting angst; it’s knowing where they are that’s soothing.

Admittedly, order is easiest with mementos and/or artifacts that I won’t be using or even accessing. A Civil War era blue shawl worn by my maternal great grandmother at her wedding in Southport, Maine. A tablecloth and napkins my mother made in the 1940s as a gift for her mother. A patchwork quilt I made with my mother in junior high as a Girl Scout project: each vacuum sealed and stored in a separate matching box, top shelf of main floor closet. Dog show plaques (ribbons and trophies discarded), dog title certificates, dog show records, VHS and 8mm videos of previous dogs I’ve shown awaiting another large project of digitizing, a swatch of hair from each dog stored in a zip-lock baggie, a few puppy teeth, one nasty foxtail that had to be surgically removed from a dog’s groin, bundled and labeled in same-size boxes. Paper items upstairs, plaques in the basement on shelves dominated by boxes of the books I’ve authored, which, despite being paper, cannot be stored in the closets upstairs. They may well rot down there.

Those things whose use is required, whether only occasionally, weekly or daily shouldn’t live in peril of being lost, but always have higher risk unless put away after each use in the same spot where they came from and can therefore always be found when needed. Scissors, hole-punches, staplers and staples, exacta knifes, packing tape, twine, twist ties, electrical ties, rubber bands, garden seeds, the metronome, saxophone reeds, saxophone repair materials, any building or painting tool, assorted hardware (organized by type and size), batteries, flashlights, light bulbs, attachments for the four different vacuum cleaners, music CDs (arranged by artist and genre) and movie DVDs (not enough of them to systematize), still also a few VHS movies that I “need” to watch every few years and haven’t yet replaced with DVDs. An exhaustive enough sentence to make my point.

I was sure I didn’t lose anything in my last move. I was accorded plenty of time, no rush to pack and move during the escrow process. So, while the new house was being painted, re-trimmed, carpeted, and a bathroom upgraded, I prepared the storage areas and closets myself. Paint, organizers, and a plan: Two closets were reassigned from the usual job of holding clothing, turned instead into structured areas for stuff from office supplies to personal files, photographs to software CDs, archived records of now dead show dogs to promotional copies of my books. The closets that still housed clothes and coats also needed sculpting to hold additional shelves for a collection of baseball memorabilia, blankets, suitcases, the few games I’ve kept, and I’ll have to end this list with the disorganized word etcetera. Then: What items could be stored on the row of shelves in the (possibly damp) basement and which required the first or second floor. Which items might need better access (from certain musical instruments to vacuum cleaners), which could be more difficult to retrieve (other musical instruments to outmoded film cameras). Lastly: which shelves had to be double-braced because they would hold books, photographs, or archived manuscripts. Which could be wire (flat objects and boxes) and which should be solid (photo albums and books). Could shelves wrap around all three walls of a closet or which side walls had to be left blank to allow drawers on center shelves to open.

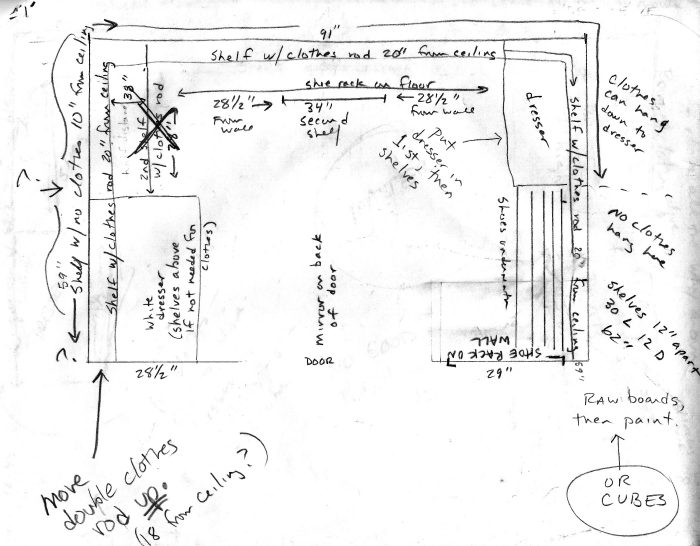

I planned the closets in pencil on graph paper. I took the design notebook with me to doctor, haircut and vet appointments and poured over the plans in waiting rooms. I had lists of measurements of everything, from how tall and wide the saxophone and trombone cases were when standing on end, how much vertical room a row of shirts would need (so I could install a dual row of shelves with clothes bar and maximize space); plus what sizes board and wire shelves did I already have — uninstalled from the previous owners and scrubbed in the tub or from my previous house, hardware saved in baggies and taped to each. This is why boys used to take drafting while girls had home economics in the ‘60s. I had neither in the ‘70s.

My diagrams almost worked. Strong enough, wide enough, space between shelves, space under shelves. Well . . . the archive and office boxes had to be tipped completely ninety degrees and sideways to be lifted up onto the highest shelves because the front edge of the shelf was too close to the front wall of the closet, leaving not enough room for a normal forty-five degree overhead straight-on placement. The triangular braces making the shelves mega sturdy, which had to be mounted into wall studs, were spaced just badly enough that my matching photo storage boxes couldn’t all fit beside each other on the shelf below. And on the lower row of the dual clothes-hanging shelves in the walk-in bedroom closet, even with short jackets assigned to hang there, hid the shoe rack mounted near the floor. Plus that lower clothes-hanging shelf proved to have a second and even more flawed design.

Meanwhile, I discovered I had lost something.

I’ve had a foot massager for over forty years. My father gave it to me for Christmas my first year of college. After four years of marching band in high school, mostly as a parade band, marching heel-first on pavement (as opposed to toe-first-on-grass when I got to college marching band), I always had aching feet. I didn’t wear flats or heels, my shoes were always tennis shoes or some kind of crepe-soled oxford (Wallabies a favorite, but I must’ve had knockoffs.) When Earth Shoes came out, I thought they were my answer. I was mostly seduced by the androgynous clodhopper styling, but the promise of returning my feet to their indigenous way of walking lured me as well. After classes, which for three-days-a-week meant after marching band rehearsal, I rushed off to my part-time job as a nurse-aide at a state ward for severely disabled children. On my feet there for another four hours. The nurses and other aides started buying their requisite white shoes in Earth Shoe styles. But when I came home with a pair, my father took a rare notice of an aspect of my wardrobe (why should he bother to notice, let alone disapprove, when I was almost always in jeans). He insisted, demanded, that I return the Earth Shoes. Yes, he had a reason, but I don’t remember. Bad for my back? My ankles? Unnatural to walk with the ball of the foot higher than the heel? Obviously I argued that my feet hurt at work, but I took the shoes back. And that Christmas my dad, who we called the great gadget-giver, gifted me a Dr. Scholl’s Foot Massager.

My feet have been better the past decade or two, since I don’t wear sneakers almost ever. Still attracted to clodhoppers, although crepe soles aren’t as common, and too many use faux leather and don’t last. Real Wallabies are over $100. But I’ve remarkably kept myself supplied in barely used Sketchers oxfords from thrift stores. Still, I always kept the massager plugged in under my desk so I could use it when I ached from long days at dog shows on concrete-floored fairground buildings or from cooking sock-footed on a tile-floored kitchen.

Then, after this last time I moved, I couldn’t find the foot massager. I didn’t seek it out until I’d been in the house for six months, was thoroughly unpacked, my closets humming along in the systemized organization born from my plans. Every few weeks I searched again in all the reasonable places, from the master bedroom upper closet shelf that held blankets, a suitcase, two office boxes of baseball memorabilia, a plastic bin with four purses I only occasionally, by particular necessity, use. To the basement in three plastic containers labeled respectively “wheeled tote bags,” “film cameras and lenses,” and a mixed bin of “jack knives, back-up cell phones, landline phones, and label-maker.” To the cabinet in the family room where there was a space for the massaging wand I’d acquired more recently beside three stacked plastic video drawers holding the BETA movies I’d taped in the ‘80s (the BETAMAX itself in a vacuumed-sealed bag in the basement for future use with a third TV mounted in front of the exercise equipment). To the supply closet in my study, to the photo and music storage closet in the other bedroom, and back to the master bedroom, where I could look up through the upper wire shelf and would see it if it were there, tucked between stacks of blankets.

Had it somehow gotten into a thrift-store donation bag? How could that happen by accident? Had I left it at the old house so it was discarded when my ex-husband moved out after me? But he would have called and, laughing, said “what’s this ancient thing, do you want it?” Dejected by lack of use, had it walked off on its own? How do people lose things when they move? How was I now one of them? How could I have something for so many decades and then suddenly it’s gone? It was just an old fashioned vibrating motor with two places to put my feet, not my identity, not my heritage, not my lineage, not my history, not my intellectual and artistic archives, not the photo record of places I’d been and people I’d been there with. But it was a gift I never would have expected in a million years, and yet so appropriate, and so comforting for so many years, and had been given to me by my parents (who must have been tired of hearing me complaining about my aching feet). Had I finally moved around too much, and too far away, that I lost part of my connection to something larger? Isn’t that what we really mean by the symbolic end of childhood?

In 2014, when my Mom went into hospice for congestive heart failure and my dad lost thirty pounds and four inches, I engaged in another obsessive search for what could be lost: my paternal genealogy.

A decade-and-a-half ago, in another period when retreating from all reality seemed not just prudent but crucial, I had pulled out a thick typed-and-stapled genealogy research project completed by my mother’s cousin, tracing my mother’s maternal lineage back to the sixteenth century Earl(s) of Mar. (Another group of distant relatives had started the project to try to lay claim to some of the Earl of Mar’s estate. It seems there was a bastard son who fled to the U.S. in the early 1700s; plenty to facilitate my escape from post 9/11 reality.) As my parenthetical excursions demonstrate, I became so enthralled in imagining the lives at each generation (enhanced by the mysteries of those who died young, men who used up multiple wives and had over a dozen children, two sisters marrying two brothers, etc.), I based a novel on my maternal genealogy, the searching, and the utter panacea in the escape of imagining. Escape which, in the novel, could not ever be complete nor be maintained.

My ancestry and cultural heritage through my father had always been the dominant “tradition” and the family we most visited in my childhood, so I’d promised I would someday trace his genealogy. I started in November, 2014. Stymied at first, I couldn’t go back father than two paternal generations. Family lore had told me that my Mazza grandfather had come from Italy when he was fifteen, which would be around 1908, but I couldn’t find a record of this Mazza family on any shipload of immigrants coming into New York from 1900 through 1920. The range was narrowed down by the federal and New York censes which recorded the morphing family from 1920 through 1940 and suggested the immigration date (which was asked on the census) as 1910. But none of the censes (in early searches) gave the name of my father’s grandmother. (My father was no help. He never knew her.) I was stuck, already, three generations back, and couldn’t even find the immigration documents.

The ancestral disarray thrumming on my mind, I paused on a bathroom trip to get from or put something into the bedroom closet, and was distracted by the now two-year-old but suddenly even more conspicuously poor closet-organizational design. I’d put the shortest jackets on that lower clothes rod, and they were still blocking the view of the shoe rack below. Sure there were shoes on the rack, but what good was it if I couldn’t see them? And for that matter, that lower clothes rack itself was a shelf that was hidden by the shirts hanging on the upper clothes rack (see arrow).

I’d planned and installed a shelf into my closet that obviously could not hold anything because not only would the shelved item cause the shirts to bunch up and wrinkle, but nothing on the shelf would be visible. As if to prove that this useless shelf was hiding there, I put my hands into the row of blouses and parted them like curtains.

And there was the forty-year-old foot massager.

As I grabbed it into my arms, the shirts swayed closed over the now empty impractical shelf. (Yes, the photo had to be re-staged.)

Did restoring this forty-year-old Christmas gift from my father allow me the breakthrough in my genealogy search? I’d like to think so. With it in its proper place under my desk (plugged in so I could flip the switch with one foot and rest my arches on the buzzing upside-down cups whenever necessary), I located the misplaced immigrants, including the missing great-grandmother, Fortunata.

With a different search on a new database (one that accessed Ellis Island records), I was able to ascertain that whoever logged the family into the manifest for the passenger ship Oceania either mis-heard the surname or in heedless sloppiness penned the letters poorly. Decades later when the name was entered into the digital files for Ellis Island, the name was read and typed as “Marza.” Uncovering this error, therefore finally finding the family on a manifest, was only possible because on the same voyage, the Oceania’s records included a list of passengers who were “held” pending a medical authorization, and the Mazza family is listed there, spelled accurately, with the correct first names for the males that I knew to look for, and all the names matched the first names of those “Marzas” handwritten on the manifest. Both lists provided the first name, Fortunata, for the individual designated “wife” to Raffaele Mazza. This women with her own beautiful name had given all three of her daughters the name Maria—Maria Grazia, Maria Elizabetta, and Maria Raffaela. By the time the US census takers were writing the family in their ledgers, the young women were going by steadily more Americanized middle names, Grace, Eliza, and Anne. Until they disappeared off the last publically available census in 1940. Probably they had married and moved and lost their original surname.

I’d have never found Fortunata if the family had not been held for medical clearance and someone actually typed that list instead of using sea-weary handwriting.

What I found in the closet, in a labyrinth of my own design, in a hiding place I’d been the one to painstakingly create, seems more than a vintage machine to ease my oft aching feet. The solace of discovering that it was not lost was then strangely equal to the odd comfort of finding those Mazzas, held on their ship for muddled bureaucratic reasons, hidden by a careless misspelling, not a flawed design.

But what did I find? A woman with seven children, three of them named Maria. A woman who died six years after settling in an immigrant neighborhood in Brooklyn, whose grandchild didn’t know her name and couldn’t remember his father or grandfather ever talking about her, even though his father named a daughter for her. A woman carrying her husband’s name so there is no way to look for her lineage. An enigmatic woman whose given name is far more beautiful and evocative than the archaic, wretchedly-colored foot massager, which also carries a man’s name. As do I—my father’s.