A long time ago, when all the grandfathers and grandmothers of today were little boys and little girls or very small babies, or perhaps not even born, Pa and Ma and Mary and Laura and Baby Carrie left their little house in the Big Woods of Wisconsin.

—Laura Ingalls Wilder, Little House on the Prairie.

The tradition goes like this: if you find the almond in the risgrynsgröt, the rice pudding, you’ll be the next one married. One Christmas, as the story goes, my great-grandfather’s family tried to engineer the serving of the rice pudding so that the youngest daughter—the youngest of nine, who was finally of marrying age—would get the almond. She got the almond, I assume, because it was not long before she was married.

In this house, among these people, in the eating of the risgrynsgröt that isn’t how she knows how to make it, I imagine that my beautiful great-grandmother is sitting back in her chair, feeling more loss than she does the gain of her husband’s family. I imagine her sitting quietly in the midst of all that family noise and I imagine she’s thinking about risgrynsgröt, about marriage, and I imagine that she’s wanting to tell Little Ethel what she’s in for when she marries.

Florence traded the lovely Swedish Shoberg for the more pedestrian-sounding Swedish Olson when she married, but she’d lost her given name as well, the melody of Florence Ida Dorothea to be known as Harry’s Florence, heavy on the Swedish Haa–rry, to differentiate her from Harry’s sister Florence. Even Harry’s sister Little Ethel needed to be somebody different from her sister-in-law, who was known in the family as Big Ethel.

Maybe when Florence and Harry met, blinded by the beauty of each other, they didn’t care about the reality of married life. Maybe all that mattered was love and desire, a Minnesotan-Swedish fairy tale, the kind that took into account the heat of Midsommar Dag and what happens on the longest day of the year in a place like Minnesota, with twilight that lasts forever. A love story that grew in that Chisago County soil, told in the language their grandparents had brought from Sweden decades ago, a language that people would still be more comfortable speaking on the street than English, well into the last decades of the 20th century. One that would linger after death, the way that it’s rumored her husband’s grandmother still haunts the big brick house in Shafer where Florence is currently eating her rice pudding.

Harry and Florence married in September 1918 and he left for the Great War five days later; their first child was born nine months to the day later.

Maybe the bedbugs on their honeymoon should have been a sign, she thinks.

Florence has a good marriage to Harry, even though it’s far from perfect. But it could be worse. She could have her mother’s life.

One day in the very last of the winter Pa said to Ma, ‘Seeing you don’t object, I’ve decided to go see the West…’ ‘Oh, Charles, must we go now?’ Ma said. The weather was so cold and the snug house was so comfortable. ‘If we are going this year, we must go now,’ said Pa. —Laura Ingalls Wilder, Little House on the Prairie.

We are a family of transplants and farmers who know what to do with roots. With the exception of my grandfather’s family, none of us have been born in the place our parents were. In hindsight, the distance and the movement matters. The Swedish language that my grandmother grew up speaking was 1860s Swedish, transplanted from Ostra Torsas, Sweden into Chisago County, where it grew again, separate from the roots it had been clipped from—and it was nearly incomprehensible, yet highly amusing, to the woman I took a Swedish class from in college. When my grandparents retired in the 1990s, they moved from the prairie of southern Minnesota to the pine forests of northern Minnesota to be closer to us and my grandmother, Florence’s younger daughter, became locally famous for her risgrynsgröt in a place more Norwegian than Swedish. And when my grandmother died and we gathered in the church’s fellowship hall for lunch after the funeral, her rice pudding was served alongside the sandwiches and bars, the recipe in her handwriting having been photocopied for anyone who wanted to take it home, and people told stories of her rice pudding.

My hometown of three hundred people was a place of potluck dinners every third Sunday at our church, a place where the bake sales were as much a religious experience as what happened on Sunday mornings, a place where the unfortunate Norwegian tradition of lutefisk transmuted itself into a more palatable autumn tradition of the Hunter’s Supper, which included other Scandinavian delicacies, a place where the Building Fund for the church addition was funded as much by lefse and fruit soup and rommegröt as it was by other donations. My grandmother’s Swedish rice pudding was as much a legend in the community as the thirty-foot fiberglass statue of a muskie on the main road through town. This was a place that if she showed up to a potluck without a double-batch of rice pudding, people complained.

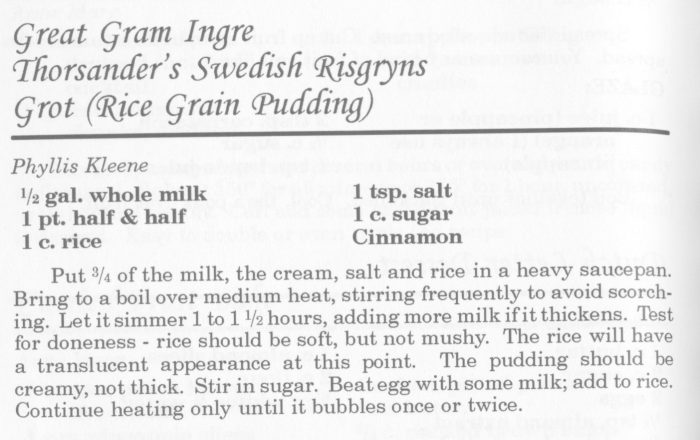

The 2005 Holy Hanna’s Manna cookbook from Bethany Lutheran Church may be the first time that my grandmother has put her recipe for rice pudding into print. She’ll write down the recipe for anyone who asks, but her handwriting is near to unintelligible. This is a recipe that doesn’t belong in print—it belongs in the cadence of my grandmother’s voice, spoken directly into your ear, as she stands behind you at the stove, watching to see if you’re stirring right.

The exacting nature of the recipe is part of the problem. Voice doesn’t translate well to font, even the swish of italics here that echoes the tone of my grandmother’s voice. In its written precision, it omits too much. When the directions are to “[stir] frequently,” there’s no mention of scraping the rice off the bottom of the pot—which would be the scorching she wants us to avoid—and there’s no opportunity for her to wax poetic about her flat-bottomed spoon. But she also doesn’t include the trick of setting the kitchen timer for ten minutes, so you don’t have to stand over the pot for an hour. She doesn’t warn the cook about tempering the egg before adding it to the hot rice mixture. Maybe she assumes that the cook will already know this. When the pudding is warmed through, the correct measure of doneness is not when “it bubbles once or twice”—the right term is “when it blups twice, it’s done.” There’s more history and tradition in that verb blup that could never be translated to bubble.

The missing almond is a tragic omission, because that’s the most important part: the tradition of the risgrynsgröt is not just in the making, but also the eating and the tradition of the culture it carries on, which is one of traditional, monogamous, nuclear families. Marriage is important. Children are important. Part of it is simple societal expectations, which almost never live up to themselves, but part has to do with the procreation necessary to keep a farm running, to bolster against infant mortality, to pass down the land to the next generation, because it’s not just important to keep the land in the family, it’s important that the land stays in the family’s name. The naming is just as important as the blood. The culture depends on it, so it’s not too far to suggest that the culture depends on the rice pudding.

Here I stand, on a Christmas morning, over Florence’s silver Wearever, making the rice pudding for our dessert later that evening, flat-bottomed wooden spoon in my hand, and wondering if it means anything that it’s the one who has always eschewed marriage and children who’s making the rice pudding, if it means anything that my nephew is allergic to dairy and eggs.

[Mrs. Scott] said she hoped to goodness they would have no trouble with Indians. Mr. Scott had heard rumors of trouble. She said, “Land knows, they’d never do anything with this country themselves. All they do is roam around over it like wild animals. Treaties or no treaties, the land belongs to folks that’ll farm it. That’s only common sense and justice.” —Laura Ingalls Wilder, Little House on the Prairie.

Florence must have learned to make risgrynsgröt from her mother-in-law, not her mother, because the recipe I know has come down that way, through this matrilineal line of Swedes I claim as mine, even though the line zigs and zags somewhat. Florence might have known how to make rice pudding, but as she was born in Nebraska to two lines of Swedes who had been living in Chisago County, Minnesota for twenty years, what she knew of rice pudding didn’t exactly translate. It, too, was a transplant. Her mother’s family had left Chisago County in 1878, to take advantage of new land, opened up when the last Pawnee was moved off their last Nebraska reservation in 1875. At least that’s what I assume, since the story has been left behind. But the timing seems to suggest a very good reason to leave where they’d established themselves in Minnesota for twenty years.

This is what happens when people and traditions are forced into landscapes where they don’t belong. When things begin to break down, other things get pushed harder and break in a different way. The soil in Nebraska, in Boone County, where Florence’s parents ended up, was not the same as what they’d left in Chisago County. Crops didn’t grow here in the same way they grew in Minnesota. There weren’t many trees, not enough to build a house from, not like the sturdy house they left in Minnesota. It wasn’t bad here in Nebraska, but it was different, and it required different ways of thinking, different ways of thinking what it means to live and what it means to survive.

Florence’s mother, Carolina, cahr-o-leena in its lovely Swedish lilt, was one of her parents’ three children who survived to adulthood. There’s a story about Carolina’s father, Oke Dahlberg, who went to town with a sack of grain on his back to have it milled into flour. While he was gone, two of his sons died of diphtheria. Their mother put the children in the woodshed until he got home.

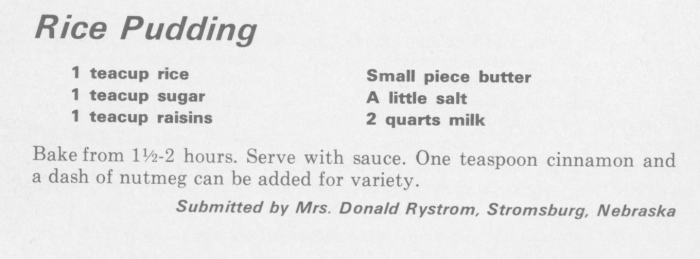

In Nebraska, they call it rice pudding, but in Swedish, it’s risgrynskaka—rice-grain-cake. What’s interesting, though, is that a recipe from this place does not match its Minnesotan equivalent. Every Nebraska cookbook I’ve found that contains a recipe for rice pudding calls for it to be baked. It’s this way in every old cookbook I’ve found, whether it’s a church cookbook, a pioneer cookbook, or any other. Every Minnesota cookbook I’ve found that contains a recipe for rice pudding calls for a stovetop cooking. (Recipes in Minnesota are split between those that call for the rice to be cooked first in water and then milk added after, usually also calling for eggs to thicken, and our risgrynsgröt, which calls for the rice to be cooked in the milk and cream, something closer to an Italian risotto.) My grandmother would tell stories of her mother putting the rice pudding on the back of the stove as she went about her day; when Harry came in from the fields, he liked his risgrynsgröt with cranberries from the local cranberry bog.

From the 1967 Nebraska Centennial Cookbook comes this recipe and it makes me smile: measuring by teacups, definitions of “small” and “little” that can only truly be understood if you know Mrs. Donald Rystrom’s family, if you know the size of her hands, her mother’s hands, her grandmother’s hands. I can see her grandmother pinching a bit of salt between her thumb and index finger, and then dropping it into the palm of her other hand, showing her granddaughter how much “a little” looks like. I can see the little girl standing on a chair, so she can reach the counter. I can hear the grandmother telling her granddaughter the tricks she’s learned about making risgrynskaka, why it’s important, maybe even that when the granddaughter is grown up and married, it’ll be her responsibility to make this for her family. I wonder how old Mrs. Rystrom is when her grandmother lets the little girl carry the risgrynskaka to the Christmas table and brag about how she did it all by herself.

What was not lost, as Mrs. Donald Rystrom’s rice pudding recipe was transplanted from her family’s voices to print, was the story she included with the recipe. She begins by establishing her family’s legitimacy in a place stolen from its original inhabitants, through the stories probably passed down in her family about the grasshoppers and the rickets. Since this is a centennial cookbook, it feels important for this family to establish that they have been a part of this place very nearly since the beginning of statehood. Every settler culture must quickly establish roots and home in any place was of utmost importance. Emotional survival, as well as political survival, depended on it. Most settler families have stories like this, stories that not only offer entertainment, but serve as cautionary tales or education for future generations, so they don’t make the same mistakes. Hardships seem to solidify one’s commitment to and understanding of a place. To ignore the importance of roots and legitimacy meant not belonging and not belonging was one step away from the grave. Nobody could survive on their own. It could not be done. The only way to survive was to be part of a community—a family, a culture, a tradition. This is the difference between merely surviving and making a life.

But to ignore the native roots that had spanned centuries in this place, solidifying the sod into something incredible to chop through to make way for crops, is terribly ironic. The metaphor of destroying those root systems to make way for the plow as the Pawnee were transplanted to another place does not escape me. There was a community in this place before the Shobergs and the Dahlbergs arrived, a land that was not empty, waiting for people who would do something with it. There was a community here that understood the moods and tantrums of this particular place, a community that understood what it meant to live and what it meant to survive, probably better than the settlers did.

That Mrs. Rystrom wrote the story about her family including an uncooked bean in their rice pudding is what links the two traditions and this is the moment that feels important to me. At one time, these two traditions were much more closely related than they were now. Rice pudding was usually a Christmas tradition among the Swedes, one that was inexpensive to make, satisfyingly rich, and offered the added benefit of being filling. Of all the recipes and stories and traditions that my Swedish ancestors passed down, the best ones are dessert and the best of the best are Christmas desserts, the best example of making something special out of the ordinary. Right now, the important thing is that bean or almond—and not just that it was there, but what it represented for that Swedish pioneer culture.

The best possible wish one could grant on a day such as Christmas would be marriage, the kind of stability that comes with life in a community.

Mary and Laura looked at each other. They knew it was no use to ask questions. They would only be told again that children must not speak at table until they were spoken to. Or that children should be seen and not heard. That afternoon Laura asked Ma what a stockade was. Ma said it was something to make little girls ask questions. That meant that grown-ups would not tell you what it was. And Mary looked a look at Laura that said, “I told you so.” —Laura Ingalls Wilder, Little House on the Prairie.

Florence’s mother, Carolina Dahlberg, was twelve years old when she moved with her family to Boone County, Nebraska. She was the only girl in a family of seven children, of whom only three survived until adulthood. Carolina was not an attractive girl, nor did she grow into an attractive woman, and I wonder if her parents worried if she would ever marry. She might have been kindly described as “sturdy,” not the delicate beauty of her two eldest daughters, Adelia and Florence. She had curly hair that obeyed no dictates but its own, eyes that were a little close together. She was not fat, but she was heavy of bone and jaw, the kind of figure that would have required massive strength on the corset strings to curve an hourglass out of her. She was the type of woman whose body was not designed to wear such things, but the only picture I have of her has Carolina looking unhappy—or, at the very least, uncomfortable—wrapped tightly into a dress that looks like something fancier than a simple farmer’s daughter would wear. Someone in her family must have had some money, to pay for both the elegant clothes and the professional photograph.

I don’t exactly know how she began a written correspondence with the man who would become her husband—three years her junior—but I wonder when the doubts surfaced, that maybe this man, this marriage wouldn’t be a good idea. The two families were neighbors and had moved from Minnesota together, so maybe their parents saw the marriage as a way to keep the family’s land together. Maybe she was pressured into it, because she wasn’t attracting other suitors and she was getting close to spinsterhood. Maybe John Edward Shoberg cornered her in the barn, backed her up against the wall, and told her that it was unlikely that anybody else would want to marry her. Maybe she worried about being a burden. Maybe her mother said to her, “You can’t live with us forever.” Maybe her father, a Civil War veteran, talked to her about duty. Maybe her family engineered the rice pudding at Christmas so that she would get the almond.

But when she decided that she would not marry him, J.E. Shoberg threatened to nail her letters to every fence post along the road. Whether that was the only threat that caused her to agree to marry him, she did, at the age of twenty-six. In their wedding photograph, neither of them look happy. I don’t know how long it was after their wedding that he started to beat her.

Her two brothers, Oscar and Emmanuel, never married. They always lived close to Carolina and her brutal husband, and their six children, and all the stories my grandmother tells are of how protective they were of their sister, how they secretly made sure that she and the children had enough money to survive. J.E. was a mean drunk, my grandmother remembers, and I imagine that without the money from Carolina’s brothers, the family probably would not have survived. I imagine that Florence looked at her parents’ marriage, what came with the risgrynsgröt, saw that Harry was nothing like her father, and took her chance to get out of the house.

Carolina died in 1938 at the age of 71, to be outlived by both of her brothers and her husband, who died at the age of 95. It’s hard for me not to wonder if he killed her, pushed her down the stairs, choked her. I wonder if Oscar and Emmanuel ever discussed the quiet disappearance of their brother-in-law, a convenient farm accident. I wonder if they ever asked Carolina if she’d like them to take care of her husband. J.E. and Carolina had seven children and I wonder how many of those children were the product of rape. Their youngest, Grace, died at the age of five, and why do I wonder if he killed her? Florence would have been thirteen when Grace died—and fourteen years later, Florence gave her name to my grandmother, Phyllis Grace. It’s easy to forget that these people of my blood were real, that they had lives just like mine, that their circumstances formed how they thought about the world, in a time much tougher and closer to the bone than mine is.

When I asked my mother what Florence was like as a person, my mother struggled to find a description I could understand, finally describing her grandmother in relation to her oldest daughter, my great-aunt Harriet: exacting, hard, could find fault with God, and fiercely competitive. My mother described Florence as trying to outdo the neighbors when threshing time came around, cooking up meat and potatoes because the men expected it at dinnertime—pork, because beef was expensive and didn’t last as long, potatoes, vegetables. Even though they had no refrigeration, Florence still would make five pies in the mornings—my grandmother remembers lemon meringue—her crusts made with lard, meringue whipped by hand, but where they got the money for lemons in Minnesota, I don’t know. This was a landscape of berries and rhubarb and cranberries, not citrus. In the afternoon, the men would expect lunch and Harry’s Florence needed to have meat and coffee ready for them and she did. Those women who weren’t able to feed the threshers well, from a house that was spotlessly clean, were obviously not raised right. It didn’t matter that this was the Depression. It didn’t matter that Harry would drink away the money on the way home from selling milk at the creamery. Some things were just not done.

When my sisters and I were growing up, my grandmother was in charge of our kitchen during the late-summer canning and freezing marathons, preserving our large garden for the winter, to be packed into two large freezers alongside the venison my father brought home every fall. We weren’t poor, especially in the context of my rural hometown, but living on one income was not possible without a garden. It still baffles my grandmother that her grandchildren, educated and employed, can food by choice, not necessity—and we do, bushels of tomatoes in the fall, applesauce, food that we buy from local farmers, so we know where it comes from, what goes into it, because we’re fortunate for the privilege of doing so. We’re the children who consider pantries and room for freezers non-negotiables of housing. We’re the children who choose not to buy baby food for our next generation, preferring to mash and freeze our own vegetables for those few short months when babies move from liquid to solid food. We’re the children who have returned to ways of thinking and living that our grandparents were happy to leave behind. We’re the children who look back at the line of women in the family and do not wonder how we got to be where we are. We are Carolina, who had to be stronger than anyone could imagine, to live for 44 years with a man who abused her, her children, to survive the death of her five year old daughter, but who found the absolute beauty in her life, the music of her children’s names: Adelia Ruth Theresia, Edna Olivia Sophia, Roy Edward Victor, Florence Ida Dorothea, Melvin George Arthur, and Grace Estella Viola. We are Florence, who made pie during the Depression, who spent five dollars for kitchen chairs one day, because they did not have chairs, and this almost caused a divorce, because they didn’t have five dollars for chairs. We are Phyllis, the first woman in her family to graduate from a four-year college in the midst of a World War. We are my mother, Barb, who passed away a year ago from cancer only found in children.

This Christmas, I wonder if it’s time to teach my niece to wield the flat-bottomed spoon and her great-great grandmother’s Wearever.

Children learn what they are taught. But genetics can only go so far—evolution works here too. It’s true that marriages in my family only turned happy after we left the land. My grandparents were married for 58 years before my grandfather died. My parents have been married for 39 years. But what’s even more interesting is that somewhere along the line, the almond in the rice pudding ceased to be about marriage. In our family, for as long as I can remember, the almond has been about a wish. Any wish.

On my niece’s first Christmas, she got her first taste of rice pudding and was not particularly impressed. She was teething, so the large carrot she’d been chewing on was more interesting. Even though she’s too young to understand, we’ll teach her about food and what it means to this family and to the community around us. Her brother, who came along three years later, is allergic to dairy and eggs, so he’ll likely never be able to taste the risgrynsgröt. Maybe, while we’re canning tomatoes, we’ll tell her about our childhood memories of canning, maybe we’ll tell her about our grandmother and her sister, maybe we’ll tell her about Harry’s Florence cooking for the threshers. Maybe we’ll tell her the story of Carolina and J.E. Shoberg. Maybe we won’t. Maybe someday we’ll tell her about what the almond used to mean in our family, but it doesn’t mean that anymore. Marriage doesn’t mean the same thing in this family that it once did, even a generation ago.

Her parents only legally married after marriage equality passed in Minnesota and her father took her mother’s name. Her aunt chooses not to marry and prefers to travel alone. Her other aunt refuses to settle for anything less than exactly what she wants.

Each of them found an almond in their rice pudding this year.